February 1, 2022 Fall/Winter 2021-22

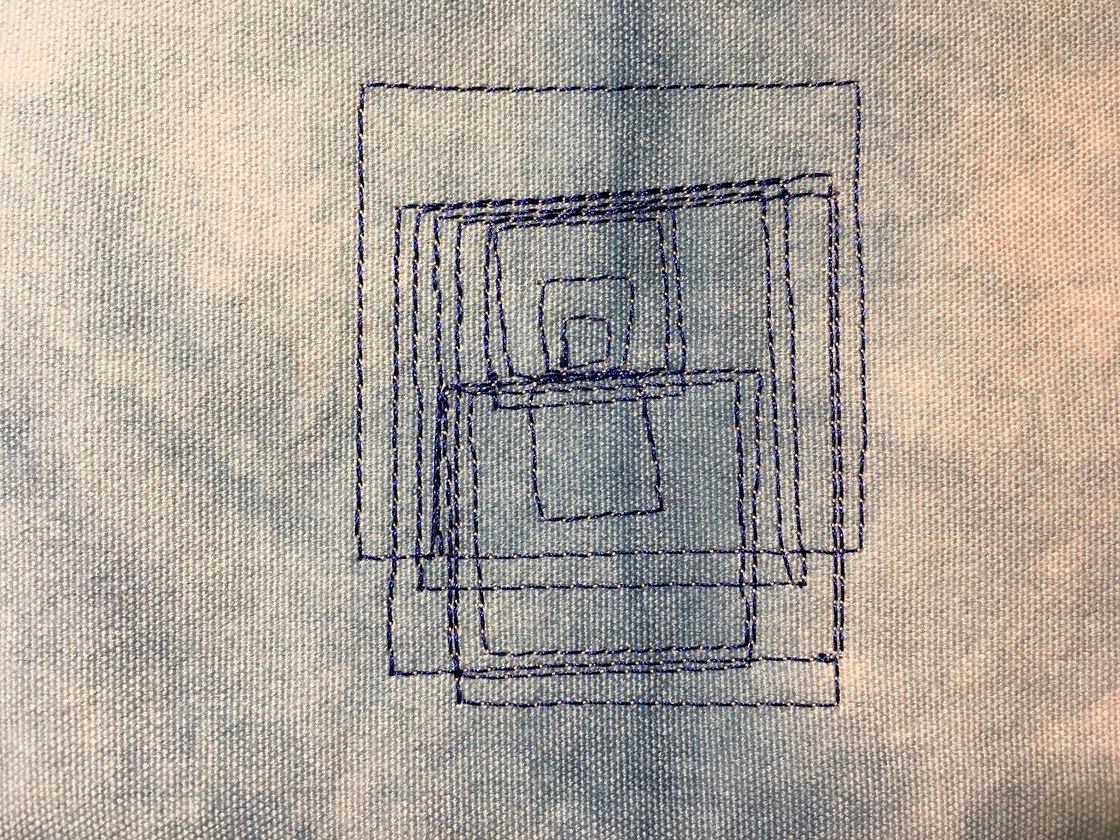

An embroidered recreation of Vera Molnar’s Trapèzes inscrits ⅕ (1971), made by participant Kate Yourke.

An embroidered recreation of Vera Molnar’s Trapèzes inscrits ⅕ (1971), made by participant Kate Yourke.Over the last 10 weeks, 20 participants gathered online to learn coding and computational art history in Recreating the Past (RTP). Each week, the class researched and developed new histories of art — bringing artists into the room together, learning about their practices, social contexts, artistic communities, all while practicing techniques for recreating artworks using code. You can meet the participants via our online webpage to see what they have been working on at the School for Poetic Computation and beyond!

SFPC has offered RTP for over seven years, and the current iteration moves the course towards new forms. While the course was created and has been taught by Zach Lieberman — for this iteration he is joined by three co-teachers: Hind Al Saad, Edgardo Avilés-López, and Murilo Polese — all former RTP participants.

Like many other fields, computational art has centered the contributions of white men in historical archives, underwriting the contributions of other people who don’t fit into the dominant culture. The Recreating the Past curriculum has been instrumental in addressing sexism and re-writing the role women have played in computational art history such as Muriel Cooper, Lillian Schwartz and Vera Molnár.

In feedback sessions about the course, participants in previous iterations of RTP have challenged the syllabus for centering mostly white American perspectives. There is a collective desire for more engagement of computational artists from other backgrounds, as evidenced by a student-organized list of artists and designers from diverse cultural and racial backgrounds in relation to topics covered in RTP in the summer of 2020.

Zach reflected on past RTP curriculum in a letter to the SFPC community when stepping down from a leadership position at SFPC:

“When I designed the class I was thinking consciously of elevating strong female voices, but I didn’t consider how the nature and material of the course paints the picture of ‘media art as a white domain.’ I take full responsibility for this shortcoming and admit that the content of this class needs to change, that it is a failure as an educator to not have a wider, more diverse and inclusive curriculum.”

The generosity of these critiques on the part of students, along with Zach’s willingness to take accountability and work with students and teachers to transform RTP, has offered an invitation for play and experimentation in this new iteration of the class.

Over the course of multiple sessions in the springtime, Zach, Hind, Edgardo and Murilo reworked the framing and content of the course, not just by expanding the canon but also by incorporating critical inquiry into what forms “recreating” the past can take: reproducing, reenacting, rethinking, reframing, and so on.

“Those working sessions in the spring were really important for re-imagining what the class could be. I feel really grateful that we had that time to work together,” Zach recounted. “It sounds silly to say, but every zoom call we’d always be smiling just thinking through and imagining new more inclusive curriculum. I’m doubly grateful that we had the chance to teach together as well.”

The new experimental iteration of the class offers a toolkit to facilitate the recreation process by centering artists brought by participants as well as all four teachers — offering more views and perspectives on what art is important.

This toolkit helped participants ask questions like:

- What was the medium the artist was using and how does it differ from today’s available medium?

- What part of society was the artist representing or actively choosing not to represent?

- What political tensions was the artist involved in? Who was on the other side?

The class also highlighted computational artists from various backgrounds in the ”Recreating the Past Artist Spotlight Series” on SFPC social media. Artists featured in this series include Saloua Raouda Choucair, Norman Pritchard, and Ulises Carrión.

One highlight of the class was a call to BYOA (bring your own artist) which connects ideas and approaches from the class to artists that students themselves choose. This year involved recreations of early computer poetry, algorithmic calligraphy, and even one student recreating their father’s artwork.

We asked participants Yadira Sanchez and Lillian-Yvonne Bertram to give some reflections on their experiences in the class:

Yadira

Q: What does ‘Recreating the Past’ mean to you?

A: ‘Recreating the past’ means to me, appreciating that what our very current westernised cultures may call obsolete technologies/tools are actually a portal to reconnect and acknowledge that creativity, technique and art are part of a larger spectrum, always connected with the culture, community and politics of the times we are “creating” art or technology.

Q: Tell us about an artist who has been influential to you in this class.

A: I really connected with Anni Albers’ and Rosa Menkman’s works. Anni made me dream, want to know more about Indigenous ancestral practices in textiles and reaffirm my application of reappropriating current technologies that fit and respect our spaces. Rosa’s work on glitch artifacts renewed my love for non-ordinary, non-perfect systems in ways that connect with my passions and dreams of non-progressive, non-upgradable technology and how glitch is a way to produce, use and perceive through our technologies.

Q: How did the toolkit help you connect with artists who are meaningful to you?

A: Above is an example of the work I did during the course where I used glitch to capture a Milpa (crop growing ancestral system in Mesoamerica) and for me represented Milpa in a glitch form as a beautiful ancestral technology that is still used by many towns and regions to eat and thrive but which is threatened by climate change and big tech greenwashing; thus employing bends and breaks as metaphors for différance and using the glitch as an exoskeleton for progress, as she recalls in the ‘Glitch studies manifesto’. How this glitch milpa changes the context and acts as if it is not logical but profoundly irrational, behaves not in the way “technology” should!

I realised more and more as the sessions progressed, that I have a tendency or inclination for making art/technology based on what it represents to me and my community(ies), like the community I grew up in, where my culture and background shape and reshape my creative process. So the toolkit really helped me reframe and rethink according to my intention.

Lillian

Q: What does ‘Recreating the Past’ mean to you?

A: [‘Recreating the Past’] means doing shallow and deep dives into how something has happened or been created, learning about methods and moments of creation, and then applying that knowledge to my own attempts at the same types of processes even if using different methods (computational methods).

Q: Tell us about an artist who has been influential to you in this class.

A: All of the artists we’ve looked at have been amazing — it’s been such a pleasure learning about new artists and their works, especially artists I wouldn’t have encountered otherwise. I really enjoyed learning about Odili Donald Odita, a Nigerian artist. I spent a lot of time looking at his works and thinking about his use of lines, geometry, and colors to create different depths and layers. I felt like I had to learn how to look at his work before I could attempt a recreation. I think the recreation I did of one of his pieces was one of my most successful in the class, and represented a breakthrough in coding but also interpreting and understanding what is happening in a piece of artwork.

Q: How did the toolkit help you connect with artists who are meaningful to you?

A: I really appreciated the way the toolkit provides a set of frameworks for engaging with artists and artworks in ways that are structured but not limiting. It also gives you a way to think about how to approach learning about and engaging with historical artworks and artists.

RTP is organized around studying different artists’s practices using today’s computational techniques to mediate a close reading of the aesthetic qualities, underlying practices and social histories of influential artists creating computer mediated work. With this frame, the class has the power to develop a canon of computer art — a group of artists and artworks of whom and which are elevated and idealized within the field. How do we as teachers and participants in classes at SFPC want to contribute to something like a canon of computer art? Who gets to decide what artists are influential?

There is much work to be done towards expanding computational art canon and the discourse surrounding it. Creating a toolkit to engage participants and members of the SFPC community in the process of compiling a more inclusive archive is a small step forward. It will take the whole community to create a database of artists who are more representative of the gradation of cultural backgrounds, political movements, and art practices that make our rich and complex community beautiful. We’re grateful for the current teachers and participants for moving us in that direction!

- Keep up with Recreating the Past and other classes on Instagram and Twitter.

- Donate to our scholarship fund to help us grow towards becoming a beautiful school that can offer free and low cost classes and events in the future.